EducationHigher Ed

In its press release, the Department of Education touts the $9,000 gap between the average earnings of graduates of public and for-profit career college programs with the assertion “public colleges pay off.” This data point will certainly be deployed to justify the Department’s uneven regulatory strategy, wherein for-profit colleges receive much tougher scrutiny than their peers in the private nonprofit and public sectors. But the earnings gap only tells part of the story.

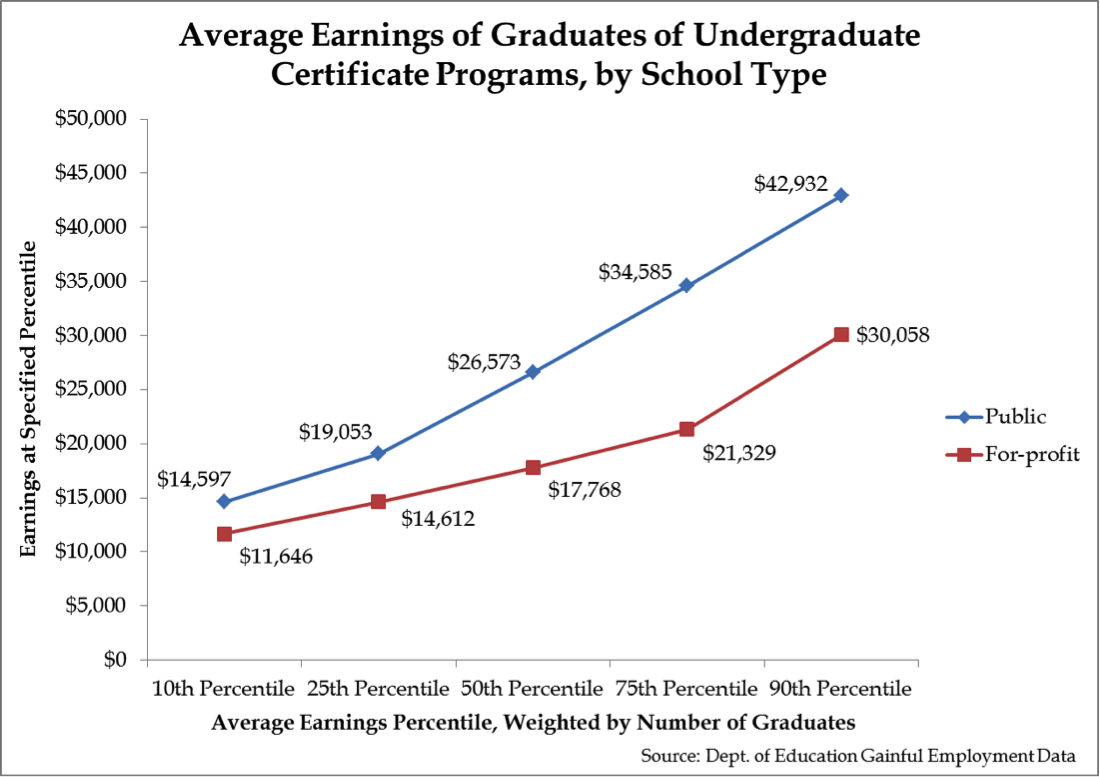

The following graph, which focuses only on undergraduate certificate programs for simplicity’s sake, shows wide variation in graduate earnings within both the public and for-profit sectors.

There are plenty of public schools which are worse than the average for-profit, and many for-profits which outperform the average public institution. Painting either sector with a broad brush is inappropriate.

More importantly, the earnings data only refer to graduates. (When I contacted the Department of Education, a spokesman told me that they were barred from releasing data on the earnings of dropouts.) Defenders of the Department’s regulatory strategy can only make a case that public colleges “pay off” for those who manage to graduate. For public colleges, graduates are a minority.

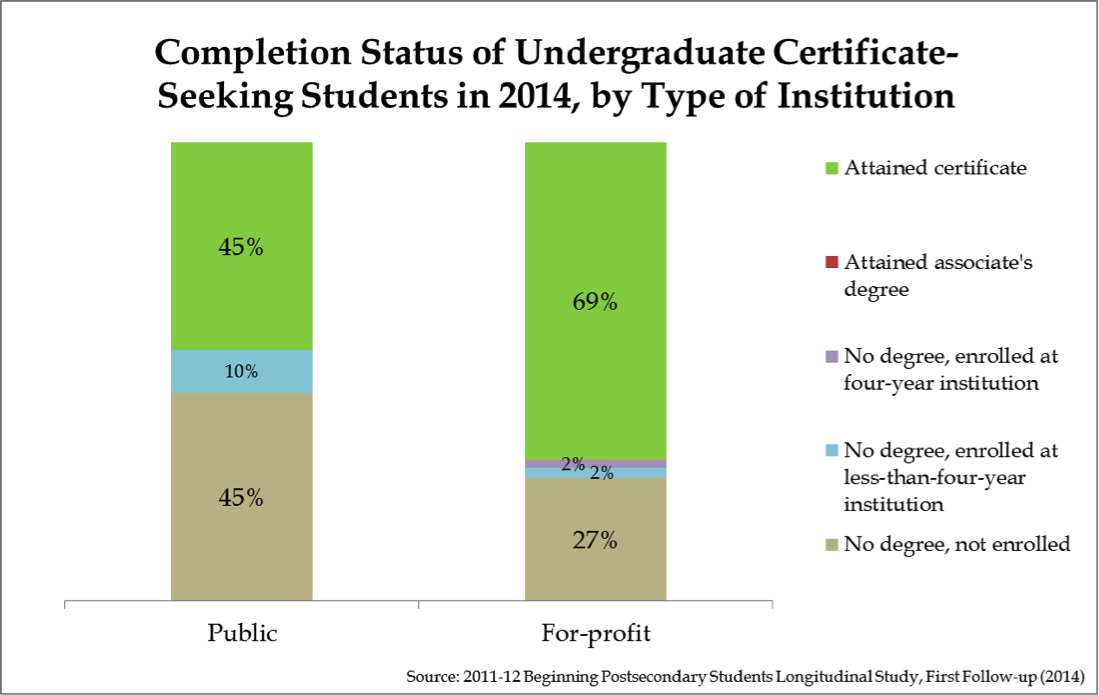

According to the Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study, only 45% of certificate-seeking students at public colleges had attained their credential three years later. However, this attainment rate was nearly 70% for comparable programs at for-profit colleges. That is a 25-point gap in favor of for-profits.

Specifically, it appears that for-profit schools have a lower bar for graduation than public schools, thus allowing more students with lower earnings potential across the finish line. Since the GE data only refer to completers, two certificate programs with identical instructional quality and student demographics could have different average earnings if one program has a higher standard for graduation. The higher-standard program will allow fewer students with low earnings potential across the finish line, which will push up the average earnings of the students who do manage to complete.

In addition, for-profit schools have a stronger incentive to admit more students who might have low earnings potential to begin with. Both public and for-profit schools are heavily subsidized. But in the case of for-profit schools, most of the subsidies generally follow the student through Pell Grants and subsidized student loans. Public schools receive those funds as well, but they also get a substantial share of revenue from direct government appropriations. To increase revenues, therefore, for-profits must go out and recruit more students. Public schools, meanwhile, will have more luck lobbying their state legislature for additional direct funds.

This is why for-profit colleges spend heavily on recruitment and advertising—more students mean more subsidies. It also explains why, according to the GE data release, the average for-profit undergraduate certificate program graduated 131 students, compared to just 30 students for comparable programs at public schools.

An odd set of incentives is at play here. Federal student aid encourages for-profit colleges to enroll as many students as possible. However, the gainful employment rule will also encourage them to graduate as few of those students as possible, letting only the highest potential earners over the finish line. (Remember, low graduate earnings put a school at risk of losing federal funding, per the gainful employment rule.) A college may want to stop a mediocre student from earning a certificate so his likely low earnings will not count against it in the GE data.

Regulators could blunt these perverse incentives by looking at graduate earnings in tandem with a school’s graduation rate. That way, colleges would have a harder time concealing their poor performance by relegating likely low earners to the pool of non-completers. But the Department of Education explicitly rejected any regulatory approach based on completions. Many public colleges, which the Department seeks to present as better alternatives to their for-profit counterparts, would fail any reasonable aid eligibility test based on graduation rate.

For-profit colleges must do better, especially given that they are the beneficiaries of billions in taxpayer money. But the idea that public colleges are superior is questionable to say the least. The outgoing Obama administration will doubtless point to the gainful employment data as a mandate to push more students into public colleges’ certificate programs, or even make the schools tuition-free. But we should really be concerned about the quality of the career college sector as a whole—public and for-profit schools alike.

This piece originally appeared on Forbes

Direct link to article: http://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/public-colleges-arent-better-bet-profits-9544.html

______________________

Preston Cooper is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute's Economics21. Follow him on Twitter here.

No comments:

Post a Comment